TV quiz shows are understandably popular. Watching someone win – or fail to win – a large sum of money can give vicarious pleasure and pain. Here is a question that I couldn’t have answered until recently…. What do the Soviet Nobel Prize winner, Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, and Harry Potter creator JK Rowling have in common?

There may be many answers, of course, but one is that they both gave Harvard Commencement speeches to graduates of that distinguished university – in 1978 and 2008 respectively, for a bonus point.

Thirty years separate the two speeches, and a further 16 years have passed since. Yet many of the words of these literary giants ring true today.

As you might expect of a Russian writer in exile, Solzhenitsyn’s message is sober. The timbre of his words would not be out of place for an Old Testament prophet.

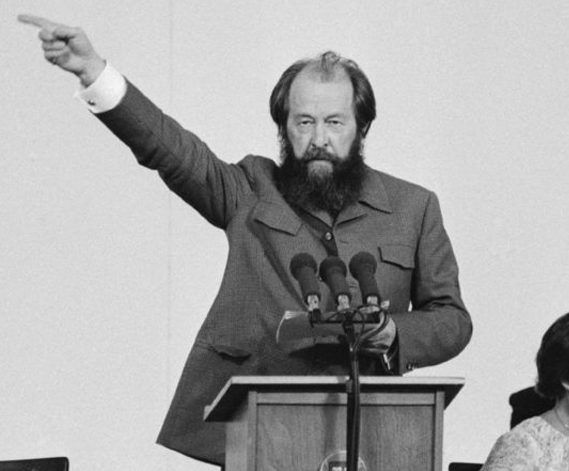

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn delivers his speech at Harvard on 8th June 1978

JK Rowling at Harvard in 2008

By Ken Noble

By contrast, Rowling’s address is more personal and contains humour, with references to the wizarding world that she envisioned. Perhaps unsurprisingly she emphasises the importance of imagination. But she sees it not just as a tool for writing but as part of learning to empathise with others. She talks of a formative time in her early 20s when she worked with Amnesty International. Some of the stories of suffering she heard there gave her nightmares. Yet, she says, ‘I also learned more about human goodness at AI than I had ever known before…. The power of human empathy, leading to collective action, saves lives and frees prisoners.’

In this context, Rowling quotes the ancient Greek writer, Plutarch: ‘What we achieve inwardly will change our outer reality.’

Solzhenitsyn declares that Western society is not an attractive alternative to what was at the time the Soviet system. ‘A decline in courage may be the most striking feature that an outside observer notices in the West today,’ he says. ‘Such a decline in courage is particularly noticeable among the ruling and intellectual elites, causing an impression of a loss of courage by the entire society.’

He attributes this ‘loss of courage’ essentially to the fact that ‘every citizen has been granted… freedom and material goods in such quantity and of such quality as to guarantee in theory the achievement of happiness…. So who should now renounce all this, why and for the sake of what should one risk one’s precious life in defence of the common good…?’

He goes on to blame this materialistic approach to life for other Western failings.

Further on, he says: ‘This tilt of freedom toward evil has come about gradually, but it evidently stems from a humanistic and benevolent concept according to which man… does not bear any evil within himself, and all the defects of life are caused by misguided social systems, which must therefore be corrected.’

The crux of his argument, I think, comes in this passage: ‘… the mistake must be at the root, at the very foundation of thought in modern times. I refer to the prevailing Western view of the world which was born in the Renaissance and has found political expression since the Age of Enlightenment. It became the basis for political and social doctrine and could be called rationalistic humanism or humanistic autonomy: the proclaimed and practised autonomy of man from any higher force above him.’ This humanistic way of thinking did not see any higher task than the attainment of happiness on earth. ‘It started modern Western civilization on the dangerous trend of worshipping man and his material needs.’

Those who watch the TV quiz shows and the adverts that punctuate them, may see echoes of what the Russian intellectual giant is saying. The overriding message is that fulfilment comes from a new car, a hamburger, opening a bank account, planning your funeral and any number of other consumer products. Clearly, there is nothing intrinsically wrong with such goods. But it is hard to disagree with Solzhenitsyn’s diagnosis that we all too easily expect material goods to meet our deepest needs.

As we approach Easter, it is timely to reflect on the alternative that it offers. It reminds us of a time when the most powerful force in the universe showed by example that he wants people to choose the way of love and self-sacrifice over ‘self’. Christ, the Messiah whom the Jews expected to liberate their nation from the Roman occupiers, chose a different path. He wanted to liberate all humankind from our materialism and self-seeking to build a kingdom on Earth where God’s will is done. It is the way, not just of courage, but of faith. Faith that God will fulfil his promise to guide and resource those who put him first.

Ken Noble has been working and volunteering with Initiatives of Change since 1971, having had ‘a profound about-turn’ in his life whilst studying physics at Imperial College, London, in 1969.